2. 中物院高性能数值模拟软件中心, 北京 100088

2. CAEP-SCNS, Beijing 100088, China

高聚物粘结炸药(PBX)是由颗粒性主体炸药(如HMX)和高聚物粘结剂、增塑剂、钝感剂等经一定工艺压制而成[1-2], 如PBX-9502炸药是95%的TATB晶粒与5%的粘结剂Kel-F800组成的复合材料[4]。最近几十年, 由于低速撞击下结构安全性和可靠性受到政府与工程界的高度重视, PBX炸药的破坏问题也备受学术界关注[5-12]。

通常认为低速撞击下炸药的点火机制包括:弹塑性或粘弹塑性变形、损伤与破坏、裂纹萌生与发展、塑性功局域化及塑性功转化为热、热传导等[13]。从试验观察发现, 含能材料的塑性变形与后继开裂问题, 直接影响了反应演化(如增加表面积会加速燃烧率)以及响应等级[14]; 材料内部的非均质损伤对炸药的力学性能及感度影响很大, 裂纹扩展也将直接影响到结构完整性[15-16]。因此, 研究PBX的裂纹产生及扩展, 对正确认识这种材料对机械刺激的响应非常必要, 同时也为评估裂纹发生的风险、研发裂纹抑制技术等提供理论支撑。

材料力学性能试验表明, 不同应力状态下PBX表现出不同的力学特性[17-19], 这给数值建模带来很大的困难[20-22]。本研究采用应力状态相关的强度模型、非关联流动法则, 描述材料在复杂应力状态下的非线性本构行为。同时, PBX在破坏模式方面表现出脆性/准脆性特点, 这种材料即使整体上承受压缩载荷, 但由于材料内部存在非均质(如微孔洞)特性[23-24], 在外部压应力作用下, 材料内部微孔洞附近产生局部的拉伸裂纹, 随着载荷发展微裂纹进一步演化、扩展, 最终导致材料或结构的整体破坏[25-27]。在模拟PBX脆性拉伸裂纹行为方面, 通常方法有:连续介质损伤力学的数值模拟方法[28-29]、直接数值模拟方法[30]、以及多尺度[31]或细观数值模拟方法[32], 以及扩展有限元(XFEM)[33-37]。由于XFEM在模拟裂纹时无需对齐网格、裂纹扩展计算时无需重新划分网格等优点, 目前备受学术界关注。本研究利用XFEM方法, 针对PBX带孔板压缩破坏试验[26], 分析PBX-9502炸药的启裂与扩展, 在材料损伤与破坏方面, 采用cohesive模型。

2 XFEM基本思想XFEM是一种解决断裂力学问题的新的有限元方法, 首先由Belytschko和Black[38]提出, 该方法基于单位分解[39], 将常规有限元法进行了扩展, 采用独立于网格剖分的思想解决有限元中的裂纹扩展问题, 在保留传统有限元所有优点的同时, 并不需要对结构内部存在的裂纹等缺陷进行网格划分。XFEM是迄今为止求解不连续问题最有效的数值方法, 它在标准有限元框架内研究问题, 保留了有限元方法的所有优点, 因此XFEM成为目前裂纹扩展模拟的主要方法之一, 也代表了计算力学数值方法近十多年来的主要进展。XFEM在处理裂纹时, 无需对齐网格, 裂纹扩展也无需重新划分网格, 而且稀疏网格也可以得到高精度数值解。XFEM这些优点使得这一方法在近十多年的计算力学界十分活跃[33, 35]。

在分析断裂问题中, XFEM引入强化基函数, 包括:裂尖附近渐进函数, 以刻画裂尖附近的应力奇异性; 不连续函数, 以表征跨越裂纹面的位移跳跃。本研究在裂纹张开与移动的计算中, 采用内聚力模型[40]和虚拟节点方法[41-42], 即在XFEM方法的框架中, 引入单元材料的拉伸-分离的内聚行为, 以模拟裂纹的萌生及扩展过程。在材料破坏方面, 采用内聚力方法; 在裂纹行为方法, 基于XFEM模拟方法, 这样结合起来, 可以模拟材料内裂纹产生及沿任意路径分析的扩展过程, 而且裂纹扩展并不必强制沿着单元边界。

3 基于XFEM的内聚力模型Cohesive模型属于损伤模型, 最先由Barenblatt[40]引入, 使用拉伸-分离法则来模拟原子晶格的减聚力, 避免了裂纹尖端的奇异性[43]。Cohesive模型与有限元方法结合首先被用于混凝土计算和模拟, 后来也被引入金属、陶瓷、复合材料等。Cohesive界面/单元须服从Cohesive分离法则, 包括粘塑性、粘弹性、破裂、纤维断裂、动力学失效及循环载荷失效等行为。典型的分离法则有Needleman律[44]、Hillerborg律[45]、Bažant律[46]。

本研究的裂纹扩展分析中, 采用了基于XFEM的内聚片段法, 应用了线弹性拉伸-分离模型、损伤启动准则和损伤演化律。在线弹性拉伸-分离模型中, 假设初始为线弹性行为, 后跟损伤启动与演化。线弹性行为表示为裂纹单元的内聚应力t与张开位移δ之间的线性关系, 即:

| $t = K\delta $ | (1) |

式中:

| $\begin{array}{l} t = {[{t_{\rm{n}}},{t_{\rm{s}}},{t_{\rm{t}}}]^T}\\ \delta = {[{\delta _{\rm{n}}},{\delta _{\rm{s}}},{\delta _{\rm{t}}}]^T}\\ K = {\rm{diag}}[{K_{{\rm{nn}}}},{K_{{\rm{ss}}}},{K_{{\rm{tt}}}}] \end{array}$ | (2) |

tn为法向应力分量, tn和tt为两个切向应力分量, 相应的分离量分别为δn, δs, δt。法向与切向刚度分量间不存在耦合现象:纯法向分离量并不会引起切向内聚力, 纯切向滑动也不会引起法向内聚力。刚度阵中的分量Knn, Kss, Ktt可通过强化单元的弹性参数计算。

在模拟拉伸开裂时, 采用最大主应力准则作为启裂准则, 即当

| $f=\left\{ \frac{<{{\sigma }_{\text{max}}}>}{\sigma _{\text{max}}^{0}} \right\}=1$ | (3) |

满足时, 裂纹启动(启裂)。式中σmax0为最大许可主应力, <·>为Macaulay括号。

采用标量损伤变量D∈[0, 1]描述内聚刚度退化率, 即损伤演化律, 以表征裂纹面与裂开单元边之间交集部分的整体平均损伤程度。在裂纹张开过程采用损伤演化方程描述, 采用能量形式的线性或指数型演化方程:

| ${\rm{d}}D = \frac{{T(\delta ){\rm{d}}\delta }}{{{G_{{\rm{eqC}}}}}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {\frac{{{T_{{\rm{max}}}}(1 - \delta /{\delta _{{\rm{max}}}}){\rm{d}}\delta }}{{{G_{{\rm{eqC}}}}}}}\\ {\frac{{{T_{{\rm{max}}}}{\rm{exp}}(\delta /{\delta _{{\rm{max}}}}){\rm{d}}\delta }}{{{G_{{\rm{eqC}}}}}}} \end{array}} \right.$ | (4) |

式中, GeqC为等效的临界断裂能释放率, J·m-2, 采用BK幂律模型[47]:

| ${G_{{\rm{eqC}}}} = {G_{{\rm{ⅠC}}}} + ({G_{{\rm{ⅡC}}}} - {G_{{\rm{ⅠC}}}}){\left( {\frac{{{G_{{\rm{Ⅱ}}}} + {G_{Ⅲ}}}}{{{G_{Ⅰ}} + {G_{{\rm{Ⅱ}}}} + {G_{Ⅲ}}}}} \right)^n}$ | (5) |

受损材料后, 方程(1) 中的法向与切线应力分量表示为:

| $\begin{array}{l} {t_{\rm{n}}} = (1 - D){T_{\rm{n}}}\\ {t_{\rm{s}}} = (1 - D){T_{\rm{s}}}\\ {t_{\rm{t}}} = (1 - D){T_{\rm{t}}} \end{array}$ | (6) |

式中, 当法向受压缩即Tn<0时, 不产生裂纹, 即tn=Tn。Tn、Ts和Tt分别为无损线弹性情况下预测的法向、切向应力分量。为了描述跨越界面同时存在法向与切线分离时的损伤演化, 采用有效分量:

| ${{\delta }_{\text{max}}}=\sqrt{<{{\delta }_{\text{n}}}{{>}^{2}}+\delta _{\text{s}}^{2}+\delta _{\text{t}}^{2}}$ | (7) |

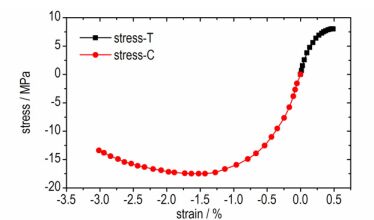

根据TATB基炸药变形特征, 如50 ℃温度下准静态拉、压不对称性[19], 如图 1所示, 本研究采用压力相关的屈服面、非关联流动法则以及应力状态相关的拉、压加权函数, 来描述复杂应力状态下材料的力学行为, 模型中引入拉伸与压缩试验数据。

|

| 图 1 TATB基炸药在50 ℃下准静态拉、压应力-应变曲线[19] Fig.1 Quasi-static stress-strain curve of TATB based explosive in tension and compression at 50 ℃[19] |

PBX在弹性变形段, 采用线弹性本构模型描述, 假设拉压模量相同。在塑性变形阶段, 由于PBX材料为内聚摩擦材料, 围压对其力学性能有影响, 因此在屈服函数中需引入应力张量第一不变量(或流体静压)。本研究借鉴了Lubliner等人[48]研究, 后经Lee和Fenves[49]进行了改进, 主要考虑了拉伸与压缩下强度差异, 屈服面的演化由两个独立演化参量

| $\begin{array}{l} F(\sigma ,{{\tilde \varepsilon }^{\rm{p}}}) = \frac{1}{{1 - \alpha }}[q - 3\alpha p + \beta ({{\tilde \varepsilon }^{\rm{p}}})\left\langle {{{\hat \sigma }_{{\rm{max}}}}} \right\rangle - \gamma \left\langle { - {{\hat \sigma }_{{\rm{max}}}}} \right\rangle ] - \\ \quad \quad \quad \quad {{\hat \sigma }_{\rm{c}}}({{\tilde \varepsilon }^{\rm{p}}}) = 0 \end{array}$ | (8) |

式中, σ为应力张量,

| $\begin{array}{l} \alpha = [({\sigma _{{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{0}}}}}/{\sigma _{{{\rm{c}}_{\rm{0}}}}}) - 1\left] / \right[2({\sigma _{{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{0}}}}}/{\sigma _{{{\rm{c}}_{\rm{0}}}}}) - 1],\\ \beta = [{\sigma _{\rm{c}}}(\tilde \varepsilon _{\rm{c}}^{\rm{p}})/{\sigma _{\rm{t}}}(\tilde \varepsilon _{\rm{t}}^{\rm{p}}](1 - \alpha ) - (1 + \alpha ),\\ \gamma = 3(1 - {K_{\rm{c}}})/(2{K_{\rm{c}}} - 1); \end{array}$ |

采用材料的摩擦角计算α=tanφ/3, 根据文献[50]中试验数据, 本研究选取20°;

与金属材料不同的是, 内聚摩擦类材料表现出剪胀特性, 需采用非关联流动法则[51]:

| ${{\dot \varepsilon }^{\rm{p}}} = \dot \lambda {\nabla _{\bar \sigma }}\mathit{\Phi }\left( \sigma \right) = \dot \lambda \frac{{\partial G\left( \sigma \right)}}{{\partial \sigma }}$ | (9) |

| $G = \sqrt {{{(e{\sigma _{{{\rm{t}}_{\rm{0}}}}}{\rm{tan}}\psi )}^2} + {q^2}} - p{\rm{tan}}\psi $ | (10) |

式中,

| ${\rm{d}}\sigma = (C - \frac{1}{h}\nabla F \cdot C \otimes C \cdot \nabla G):{\rm{d}}\varepsilon $ | (11) |

式中,

针对拉压异性材料的塑性应变

| ${{{\dot{\tilde{\varepsilon }}}}^{\text{p}}}\text{=}\left[ \begin{matrix} \dot{\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{\text{t}}^{\text{p}} \\ \dot{\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{\text{c}}^{\text{p}} \\ \end{matrix} \right]=\hat{h}\left( \hat{\sigma },{{{\tilde{\varepsilon }}}^{\text{p}}} \right)\cdot {{{\dot{\tilde{\varepsilon }}}}^{\text{p}}}$ | (12) |

式中,

| $r\left( {\hat{\sigma }} \right)=\frac{\text{def}\sum\nolimits_{i=1}^{3}{\left\langle {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{i}} \right\rangle }}{\sum\nolimits_{i=1}^{3}{\left| {{{\hat{\sigma }}}_{i}} \right|}}$ | (13) |

式中,

根据TATB钝感炸药相关试验数据[17, 50, 53], 本研究采用表 1的材料模型参数。

| 表 1 50 ℃下PBX-9502材料参数 Tab.1 Material parameters of PBX-9502 at 50 ℃ |

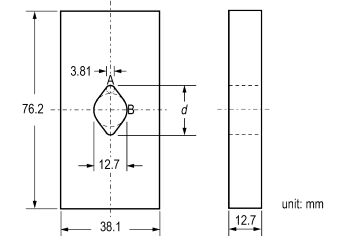

本研究采用文献[26]的试验模型。试验材料为TATB基钝感炸药, 试验温度为50 ℃, 试验采用单轴压缩加载, 加载速率为1.27 mm·min-1。试件几何为中心带椭圆形孔板, 如图 2所示。板尺寸的高×宽×厚为76.2 mm×38.1 mm×12.7 mm, 中心孔由四段直线和两段弧线围成, 弧线段的直径为12.7 mm和3.81 mm, 孔的高度d为19.05 mm, 孔的上端顶点为A, 侧边顶点为B。数值模拟的网格为四边形平面应力单元, 单元尺寸约0.5 mm; 采用最大主应力和断裂能准则, 无需预置初始裂纹。

|

| 图 2 PBX-9502带孔板受压下断裂试验试件尺寸 Fig.2 Specimen plate with cavity for fracture experiment on PBX-9502 subject to compression |

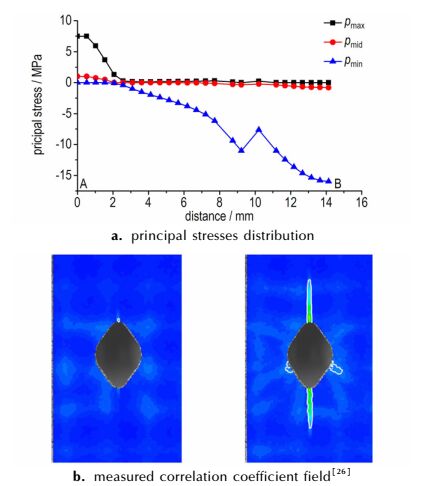

采用PANDA_Fracture进行XFEM分析, 计算结果表明, 板在整体压缩作用下, 中心孔的四周受力与变形很不均匀, 在孔的上、下两端点承受的第一主应力为拉应力, 且沿孔内壁分布为最大点。图 3a为拉伸裂纹产生前孔内壁从顶点A到侧边B点之间、沿孔内壁的主应力分布; 可见A点所受的第一主应力为最大, B点所受的第三主应力和剪应力为最大(绝对值), 因此开裂破坏模式首先在A点萌生, 裂纹方向将与最大主应力方向垂直; 其次在B点将会萌生剪切破坏模式; 从实测相关系数场图 3b中也可以证实这一结果[26]。

|

| 图 3 试件椭圆形孔内壁应力分布图 Fig.3 stress distribution on the inner wall of elliptical hole in specimen |

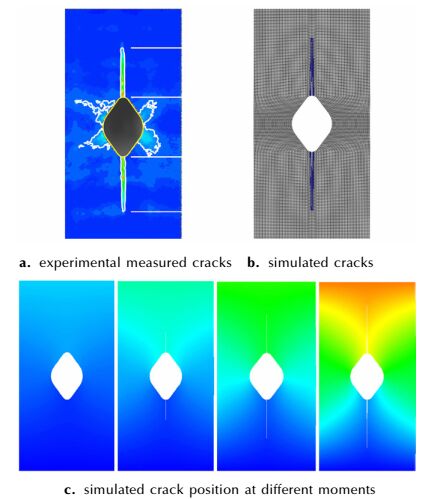

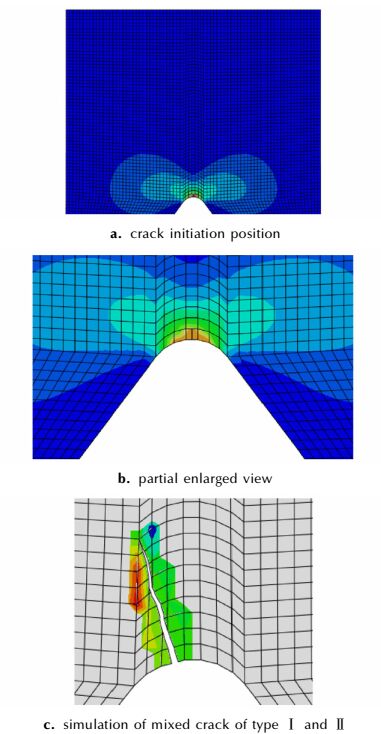

数值模拟表明, 在外部压应力作用下, 试件内部孔洞附近产生非均匀变形场与应力场, 导致应力集中或高的应力梯度, 当局部应力如拉应力到达材料破坏应力时, 产生局部的拉伸裂纹, 随着外载于变形进一步发展, 裂纹在萌生处迅速沿着最大主应力区域扩展, 最终形成两条宏观裂纹, 如图 4所示, 其中图 4a为试验图, 图 4b为数值模拟获得的裂纹最终图, 图 4c为典型时刻的裂纹位置图。图 5为数值模拟, 其中孔内壁A点的拉伸裂纹萌生及裂纹方向图像见图 5b。图 5c为混合裂纹预测图:当把端面位移载荷同时施加到纵向与横向时, 从孔内壁顶点附近产生Ⅰ-Ⅱ型混合裂纹。

|

| 图 4 PBX-9502带孔板状试件在整体压缩下启裂及裂纹路径 Fig.4 Crack initiation and growth of PBX-9502 platy specimen with cavity subjected to overall compression |

|

| 图 5 PBX-9502裂纹萌生点与裂纹方向的数值模拟 Fig.5 Simulation of crack initiation location and direction of PBX |

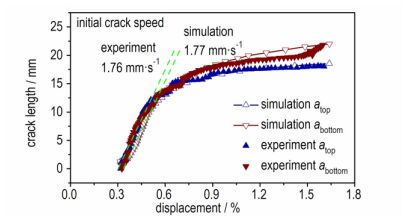

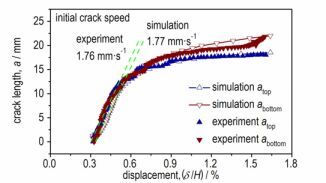

图 6为启裂时间、裂纹扩展速度、裂纹扩展历程的数值模拟结果与试验[26]对比。整体上数值模拟给出的裂纹发展趋势与试验结果相吻合, 如上、下裂纹时程的整体走势和拐点, 启裂时刻均在δ/H=0.32%(约0.2 min), 裂纹初期扩展速度的试验值为1.76 mm·s-1, 数值模拟值为1.77 mm·s-1。这说明基于XFEM和内聚模型的方法, 对Ⅰ型裂纹的产生、扩展的模拟是可行的; 在裂纹产生、扩展等整体发展规律上, 数值模拟可以给出好的预测。但在一些细节上, 如裂纹产生后, 数值模拟得到的裂纹扩展较实测值有一个滞后; 且裂纹发展后期, 模拟与实测的裂纹位置有一定的偏差。可能的原因有:

|

| 图 6 启裂时间与裂纹扩展速度、裂纹扩展历程的关系曲线 Fig.6 Crack initiation moment, initial crack speed and growth history curves |

(1) 试验测试裂纹位置时, 理论上需要足够高的分辨率以识别裂纹、捕捉裂尖位置, 但在实际测量中很难做到, 这可能导致裂纹位置、长度等的测试值与实际有差异。

(2) 目前采用的XFEM计算, 简化的算法导致裂纹扩展时一次性地穿越一个单元, 显式上单元内裂纹的速度为无穷大, 当网格不是足够精细时, 会导致裂纹扩展在时间预测方面有一定的误差。

(3) 在模拟裂纹间断面时材料损伤破坏导致材料软化、刚度劣化, 数值算法遇到收敛困难; 为克服这种困难, 在内聚本构模型的算法中引入表征粘性系统松弛时间的粘性系数, 进行粘性正则化处理。这也导致材料破坏模拟方面出现很小程度的松弛效应。

(4) 由于PBX炸药具有细观非均质特性, 力学参数有一定的随机分散性, 而且在加工过程中, 孔周边受到一定程度的损伤, 可能导致裂纹扩展曲线上出现局部的跳跃, 如下端曲线, 本研究的数值方法没有计及这些影响。

6 结论(1) PBX-9502带孔板在整体压应力条件下, 孔洞周围产生非均匀应力与变形场, 导致局部应力集中; 当拉应力到达材料破坏强度时, 局部位置萌生开裂破坏模式; 随着载荷与变形的发展, 裂纹单元损伤继续演化, 当达到临界值时, 裂纹进一步张开, 沿着最大主应力区域扩展, 最终导致材料整体开裂破坏。这是含孔洞板受压开裂机理, 减小孔洞内壁或周边的拉伸应力集中的措施, 将有助于防止开裂破坏。

(2) 整体上数值模拟给出的裂纹发展趋势与试验结果相吻合, 包括裂纹时程的整体走势和拐点、启裂时刻、裂纹初期扩展速度等; 表明基于XFEM和内聚模型的方法, 对 Ⅰ型裂纹的产生、扩展的模拟是可行的; 在裂纹产生、扩展等整体发展规律上, 数值模拟可以给出较好预测。

(3) 由于PBX炸药具有细观非均质特性, 其宏观上力学参数有一定的分散性或随机性, 因此良好的数值预测需要统计试验数据作支撑, 将材料参数的统计特性引入到数值模拟中。

| [1] | Skidmore C B, Phillips D S, Howe P W, et al. The evolution of microstructural changes in pressed HMX explosives[C]// Colorado: Short J M, Kennedy J E.Proceedings of the 11th Detonation Symposium. Snowmass Village, 1998: 556-564. |

| [2] | Ye S, Tonokura K, Koshi M. Energy transfer rates and impact sensitivities of crystalline explosives[J]. Combustion & Flame, 2003, 132(1-2): 240-246. |

| [3] | Clements B E, Mas E M. A theory for plastic-bonded materials with a bimodal size distribution of filler particles[J]. Modelling & Simulation in Materials Science & Engineering, 2004, 12(12-15): 407-421. |

| [4] | Baer M R. Modeling heterogeneous energetic materials at the mesoscale[J]. Thermochimica Acta, 2002, 384(1-2): 351-367. DOI:10.1016/S0040-6031(01)00794-8 |

| [5] | Palmer S J P, Field J E, Huntley J M. Deformation, strengths and strains to failure of polymer bonded explosives[J]. Proceedings Mathematical & Physical Sciences, 1993, 440(1909): 399-419. |

| [6] | Li M, Zhang J, Xiong C Y, et al. Damage and fracture prediction of plastic-bonded explosive by digital image correlation processing[J]. Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 2005, 43: 856-868. DOI:10.1016/j.optlaseng.2004.09.003 |

| [7] | Liu Z W, Xie H M, Li K X, et al. Fracture behavior of PBX simulation subject to combined thermal and mechanical loads[J]. Polymer Testing, 2009, 28: 627-635. DOI:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2009.05.011 |

| [8] | Chen P, Xie H, Huang F, et al. Deformation and failure of polymer bonded explosives under diametric compression test[J]. Polymer Testing, 2006, 25(3): 333-341. DOI:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2005.12.006 |

| [9] | Chen P, Huang F, Ding Y. Microstructure, deformation and failure of polymer bonded explosives[J]. Journal of Materials Science, 2007, 42(13): 5272-5280. DOI:10.1007/s10853-006-0387-y |

| [10] | Pengwan Chen, Zhongbin Zhou, Shaopeng Ma, et al. Measurement of dynamic fracture toughness and failure behavior for explosive mock materials[J]. Front Mech Eng, 2011, 6(3): 292-295. |

| [11] | Li Jun-Ling, Fu Hua, Tan Duo-Wang, et al. Fracture Behaviour Investigation into a Polymer-Bonded Explosive[J]. Strain, 2012, 48: 463-473. DOI:10.1111/str.2012.48.issue-6 |

| [12] | Zubelewicz A, Thompson D G, Ostojastarzewski M, et al. Fracture model for cemented aggregates[J]. AIP Advances, 2013, 3(1): 3275 |

| [13] | Danzhu Ma, Pengwan Chen, Qiang Zhou, et al. Ignition criterion and safety prediction of explosives under low velocity impact[J]. Journal of Applied Physics, 2013, 114(11): 405-408. |

| [14] | Berghout H L, Son S F, Skidmore C B, et al. Combustion of damaged PBX 9501 explosive[J]. Thermochimica Acta, 2002, 384(1-2): 261-277. DOI:10.1016/S0040-6031(01)00802-4 |

| [15] | Bennett J G, Haberman K S, Johnson J N, et al. A constitutive model for the non-shock ignition and mechanical response of high explosives[J]. Journal of the Mechanics & Physics of Solids, 1998, 46(12): 2303-2322. |

| [16] | Dienes J K, Zuo Q H, Kershner J D. Impact initiation of explosives and propellants via statistical crack mechanics[J]. Journal of the Mechanics & Physics of Solids, 2006, 54(6): 1237-1275. |

| [17] | Belmas R, Reynier P. Mechanical behavior of pressed explosives[C]//International Symposium Energetic Materials Technology Florida, March 21-23, 1994: 360-365. |

| [18] | Ellis K, Leppard C, Radesk H. Mechanical properties and damage evaluation of a UK PBX[J]. Journal of Materials Science, 2005, 40(23): 6241-6248. DOI:10.1007/s10853-005-3148-4 |

| [19] | Thompson D G, Gray Ⅲ G T, Blumenthal W R, et al. Quasi-static and dynamic mechanical properties testing of PBX 9502: strain rate, temperature, density and processing methods[R]. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM, 2002, LA-UR-02-6592 |

| [20] | Picart D, Brigolle J L. Characterization of the viscoelastic behaviour of a plastic-bonded explosive[J]. Materials Science and Engineering, A, 2010: 7826-7831. |

| [21] | Viet Dung Le, Michel Gratton, Michael Caliez, Arnaud Frachon, Didier Picart. Experimental mechanical characterization of plastic-bonded explosives[J]. Journal of Materials Science, 2010, 45: 5802-5813. DOI:10.1007/s10853-010-4655-5 |

| [22] | Picart D, Benelfellah A, Brigolle J L, et al. Characterization and modeling of the anisotropic damage of a high-explosive composition[J]. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 2014, 131: 525-537. DOI:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2014.09.009 |

| [23] | Asay B W. Non-Shock Initiation of Explosives(Shock Wave Science and Technology Reference Library, Vol. 5)[M]. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, 2010. |

| [24] | Trumel H, Lambert P, Belmas R. Mesoscopic investigations of the deformation and initiation mechanisms of a HMX-based pressed composition[C]//USA :Proceedings of the 14th Detonation Symposium, Coeur d′Alene, , 2010. |

| [25] | Gilles Pijaudier-Cabot, Zdenek Bittnar, Bruno Gerard. Mechanics of Quasi-Brittle Materials and Structures[M]. HERMES Science Publications, Paris, 1999. |

| [26] | Liu C, Thompson D G. Crack Initiation and Growth in PBX 9502 High Explosive Subject to Compression[J]. Journal of Applied Mechanics, 2014, 81(10): 212-213. |

| [27] | Van de Steen B, Vervoort A, Napier J A L. Observed and simulated fracture pattern in diametrically loaded discs of rock material[J]. International Journal of Fracture, 2005, 131: 35-52. DOI:10.1007/s10704-004-3177-z |

| [28] | Lemaitre J, Desmorat R. Engineering Damage Mechanics-Ductile, Creep, Fatigue and Brittle Failures[M]. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005. |

| [29] | Xicheng Huang, Chengjun Chen, Gang Chen, et al. Analysis of deformation and failure of polymer-bonded explosives using coupled plastic damage model[C]//Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Composite Materials, Copenhagen, Denmar, 2015. |

| [30] | Ionita A, Clements B E, Zubelewicz A, et al. Direct numerical simulations to investigate the mechanical response of energetic materials[R]. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM, 2011, LA-UR-11-02598. |

| [31] | Toro S, Sánchez P J, Blanco P J, de Souza Neto E A, Huespe A E, Feijóo R A. Multiscale formulation for material failure accounting for cohesive cracks at the macro and micro scales[J]. International Journal of Plasticity, 2016, 76: 75-110. DOI:10.1016/j.ijplas.2015.07.001 |

| [32] | Wu Y Q, Huang F L. A micromechanical model for predicting combined damage of particles and interface debonding in PBX explosives[J]. Mechanics of Materials, 2009, 41(1): 27-47. DOI:10.1016/j.mechmat.2008.07.005 |

| [33] | Belytschko T, Black T. Elastic crack growth in finite elements with minimal remeshing[J]. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 1999, 45(5): 601-620. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0207 |

| [34] |

庄茁.

扩展有限单元法[M]. 北京: 清华大学出版社, 2012.

ZHUANG Zuo. Extended Finite Element Method[M]. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 2012. |

| [35] |

余天堂.

扩展有限单元法—理论[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2014.

YU Tian-tang. Extended Finite Element Method-Theory, Application and Programming[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2014. |

| [36] | Pommier S, Gravouil A, Combescure A, et al. Extended finite element method for crack propagation[J]. John Wiley & Sons, 2013: 173-226. |

| [37] | Tian Rong, Wen Longfei. Improved XFEM-An extra-dof free, well-conditioning, and interpolating XFEM[J]. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2015, 285: 639-658. DOI:10.1016/j.cma.2014.11.026 |

| [38] | Belytschko T, Black T. Elastic crack growth in finite elements with minimal remeshing[J]. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 1999, 45(5): 601-620. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0207 |

| [39] | Melenk J M, Babuška I. The partition of unity finite element method: Basic theory and applications[J]. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics & Engineering, 1996, 139(1-4): 289-314. |

| [40] | Barenblatt G I. The Mathematical Theory of Equilibrium Cracks in Brittle Fracture[J]. Advances in Applied Mechanics, 1962, 7: 55-129. DOI:10.1016/S0065-2156(08)70121-2 |

| [41] | Jeong Hoon Song, Areias P M A. Belytschko T. A method for dynamic crack and shear band propagation with phantom nodes[J]. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 2006, 67(6): 868-893. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0207 |

| [42] | Remmers J J C, Borst R D, Needleman A. The simulation of dynamic crack propagation using the cohesive segments method[J]. Journal of the Mechanics & Physics of Solids, 2008, 56(1): 70-92. |

| [43] | Lawn B R. Fracture of Brittle Solids(second edition)[M]. Cambridge University Press, 1993. |

| [44] | Needleman A. An analysis of decohesion along an imperfect interface[J]. International Journal of Fracture, 1990, 42(1): 21-40. DOI:10.1007/BF00018611 |

| [45] | Hillerborg A, Modéer M, Petersson P E. Analysis of crack formation and crack growth in concrete by means of fracture mechanics and finite elements[J]. Cement & Concrete Research, 2008, 6(6): 773-781. |

| [46] | Zdeněk P. Bažant. Concrete fracture models: testing and practice[J]. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 2002, 69(2): 165-205. DOI:10.1016/S0013-7944(01)00084-4 |

| [47] | Benzeggagh M L, Kenane M. Measurement of mixed-mode delamination fracture toughness of unidirectional glass/epoxy composites with mixed-mode bending apparatus[J]. Composites Science & Technology, 1996, 56(4): 439-449. |

| [48] | Lubliner J, Oliver J, Oller S, et al. A plastic-damage model for concrete[J]. International Journal of Solids & Structures, 1989, 25(3): 299-326. |

| [49] | Lee J, Fenves G L. Plastic-Damage Model for Cyclic Loading of Concrete Structures[J]. Journal of Engineering Mechanics, 1998, 124(8): 892-900. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399(1998)124:8(892) |

| [50] | Gruau C, Picart D, Belmas R, et al. Ignition of a confined high explosive under low velocity impact[J]. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2009, 36(4): 537-550. DOI:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2008.08.002 |

| [51] | Chen W F, Han D J. Plasticity for structural engineers[M]. Springer-Verlag, 1988. |

| [52] | EA de Souza Neto, D Peric', DRJ Owen. Computational methods for plasticity-theory and applications[M]. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 2008. |

| [53] | Williamson D M, Palmer S J P, Proud W G. Fracture studies of PBX simulant materials[C]//Furnish M D, Elert M, Russel T P, et al. Shock Compression of Condensed Matter-2005. American Institute of Physics, 2006, 845(1): 829-832. |

The extended finite element method coupled with cohesive model is applied to simulate the crack behaviors in the PBX platelike specimen with cavity subjected to overall compression. The crack behaviors include the trend of crack growth, feature of crack-time curve, crack initiation moment, crack′s initial speed.